Pectin makes it all possible. Pectin is one of God’s best ideas, purveyed in fruity packages. No question: God intended us to have jellies and jams and marmalade. This is why I take my marmalade straight, by the spoonful . . .

Paula Panich

Usner’s Map: A Writer and Photographer’s Survey of the New Mexico He Loves

Photographer, writer, and cultural geographer Don J. Usner was a speaker at FUZE-SW, Santa Fe, New Mexico’s first food conference, held in early November this year (2013).

He and another accomplished writer, Carmella Padilla (The Chile Chronicles: Tales of a New Mexico Harvest, and many other books) came to the podium together to address the collective memory of their New Mexican childhoods. Here is the title of their joint talk: Tales We Heard Around the Kitchen Table: Growing Up With Chiles.

It’s déclassé to harbor jealousy over the childhoods of others, but there it is. They were both full of joy and remembrance of chile harvests and extended family tables with fresh, roasted autumn-harvested chiles.

But I happened to speak to Don Usner in passing at lunchtime; he mentioned a book of his, published in 1995, and the hope he has for finding a new publisher willing to keep it in print. Here it is:

Continue readingFUZE-SW Food + Folklore in Santa Fe: Mestizaje, Chocolate in Chaco, and What We Ate ,

(This is the second of my whacky and wildly incomplete posts on the FUZE-SW Food + Folklore Conference in Santa Fe, held Nov. 8-10 at the International Museum of Folk Art.)

Here is what we had for lunch on Saturday, November 9:

Oh, it was tasty: Sweet corn custard; Jalisco sopes, Nopal salad, Poblano mole, dark chocolate tart — so delicious. A New World Cuisine lunch, prepared by the Museum Hill Cafe. (i-Phone photo; sorry so small.) New World Cuisine is the name of the exquisite exhibit on the food of the New World at the International Folk Art Museum.

Here is a description:

Continue readingFUZE-SW! Food + Folklore in Santa Fe: The Elements of the New Mexican Table

FUZE-SW 2013, Food + Folklore Festival took place November 8-10, 2013 at the International Museum of Folk Art in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

For the sixty or so people lucky enough to attend Santa Fe’s first food conference, we were treated to the thinking of the most astonishing line-up of chefs, food scholars, anthropologists, historians, poets, writers — all addressing, from many points of view, the question of how and whence and where and what — is the cooking of the Americas?

Well. It’s a very big question. But since we were sitting in Santa Fe, the capitol of New Mexico, I’m going to start my reportage of the conference with this cookbook. Fabiola Cabeza de Baca Gilbert, born near Las Vegas, New Mexico — well, her cookbook says in 1894; the New Mexico Historical Society says 1898 — first published her book, Historic Cookery in 1931. (Her great-nephew, Tom C Baca, spoke Saturday at the conference; I missed it for reasons explained in a moment.)

FUZE-SW Food +Folklore Festival, November 8-10, 2013

Greetings! I will be blogging and Instagramming all weekend from the first annual FUZE-SW Food + Folklore Festival at the Museum of International Folk Art in Santa Fe, New Mexico, where the topic of the conference will the the past and present folklore and customs that fused to make the fantastic culinary traditions of New Mexico.

Please stay tuned!

Below is information about this photo (by Kitty Leaken) from the Museum:

Chocolate Making (Implements and Ingredients)

In this image is a green ceramic chocolatero, from China, 17th c., with locking lid of iron, made in Mexico, 18th c.; a blue and white talavera (chocolate) pitcher, typical to Mexico, 1775–1810; a copper chocolate pot, used for heating and frothing, 19th c.; a talavera plate, with almonds and ground chocolate, 1750–1800; and, a wood molinillo (whisk), late 19th–early 20th c. And, then we have two grinding devices, indigenous versions of the mortar and pestle introduced by Europeans. The bowl-like, stone implement in the upper-right is a molcajete, here filled with vanilla and cinnamon; and, in the upper-left is a flat metate y mano (grinding stone and surface), filled with cocoa beans. Both are late 19th–early 20th c., and were also used to crush cocao beans, almonds, and such spices as vanilla pods and red chili, all shown here, into a powder to make traditional Mexican chocolate.

Long, long before it became a Hershey bar in 1895, a rationed item during World War II, and a antioxidant health food today, chocolate had charmed the cognoscenti, had become so coveted that it was counterfeited, and even caused a revolt.

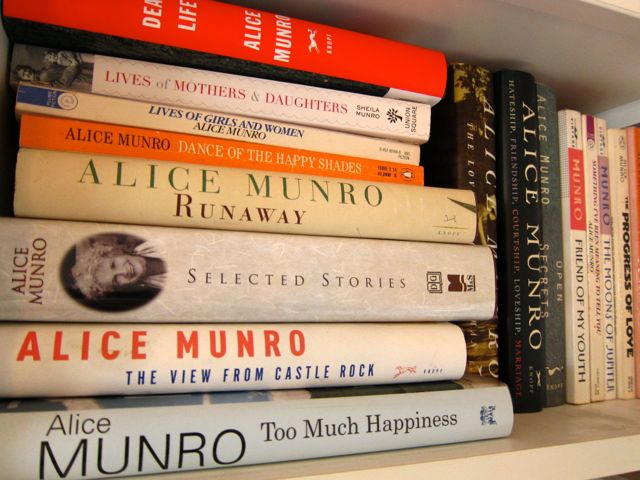

Alice Munro: My Goddess Wins the Nobel Prize

This is my Alice Munro bookshelf. Every book published, at least in this country. I began reading her a quarter of a century ago. I not only love her writing — that’s a given — but I will be forever grateful to her for the opening and clearing of my own writerly voice. She has shown what women think, how they work, how they relate to each other across generations, and what they think of men. What they really think of men. Everything is very complicated, I can tell you.

This was on the New Yorker Blog — writers you may know weighing in on her astonishing body of work. Her short stories are more resonant of life than most contemporary novels. Everyone quotes it, but it’s worth repeating: Writer Cynthia Ozick said it many years ago: She is our Chekhov. This Nobel news yesterday — it’s as good as it gets.

Margaret Atwood:

As I wrote in my introduction to her “Collected Stories”:

Through Munro’s fiction, Sowesto’s Huron County has joined Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County as a slice of land made legendary by the excellence of the writer who has celebrated it, though in both cases “celebrated” is not quite the right word. “Anatomised” might be closer to what goes on in the work of Munro, though even that term is too clinical. What should we call the combination of obsessive scrutiny, archaeological unearthing, precise and detailed recollection, the wallowing in the seamier and meaner and more vengeful undersides of human nature, the telling of erotic secrets, the nostalgia for vanished miseries, and rejoicing in the fullness and variety of life, stirred all together?

Alice and I have been friends since 1969, when her collection of stories “Dance of the Happy Shades” and my collection of poems “The Circle Game” were both published, and I slept on her floor during a visit to Victoria. A lot of Canadians began with short stories then, because it was so hard to get novels published in Canada in the sixties. We both got our start through Robert Weaver’s CBC radio show, “Anthology.” Canadians will be thrilled, Alice will be bowled over, and we will all have a party once she has made her way out of the coat closet, where she has probably gone to hide.

Julian Barnes:

Alice Munro can move characters through time in a way that no other writer can. You are not aware that time is passing, only that it has passed—in this, the reader resembles the characters, who also find that time has passed and that their lives have been changed, without their quite understanding how, when, and why. This rare ability partly explains why her short stories have the density and reach of other people’s novels. I have sometimes tried to work out how she does it but never succeeded, and I am happy in this failure, because no one else can—or should be allowed to—write like the great Alice Munro.

Sheila Heti:

In this vast country without a vast number of people, there are few (for me, anyway) cultural heroes. Glenn Gould is one of them. Alice Munro is another. I think of them all the time, actually. They represent something similar: consistency, seriousness, an uncompromising attitude, and work that is daunting, single-minded, and perfect.

She has always done what she has wanted to, in the way she has wanted to. You look at her and think, Of course, just put all of your intelligence and sensitivity and vitality into your work in a consistent way. There is nothing else. She lives in a small town, has had the same agent since the seventies, doesn’t review books or do many interviews. She seems not to waste her time. She just goes straight to what matters most.

I don’t know when I first read Munro. Probably in school. Certainly her books were always around the house. In Canada, she’s just in the atmosphere, like the Queen.

At a certain point in my early twenties, I wrote a fan letter to Alice Munro. I don’t remember what it said, but I remember how thrilled I was, many months later, to receive a card in the mail with a handwritten thank you in beautiful script, as gracious as anything. She seemed surprised, as though never before had a stranger told her that her stories could mean so much. How alive and unjaded! She must have sent out hundreds, if not thousands, of handwritten cards over the years. It showed me that a writer could be kind and still be a master. One didn’t have to play the aloof or superior game. Indeed, the best writers are probably the best because they have a surfeit of love and generosity toward the world, not the reverse.

In Canada, you can’t make a spectacle of yourself. You have to let other people make a spectacle of you for you. So it’s moving that the answer to her book “Who Do You Think You Are?,” published when she was forty-one (and it’s the question asked of any Canadian person who aspires to anything great) can be, that same number of years later, “The winner of the Nobel Prize.” Not that this would ever be her answer. But it’s wonderful that it can be ours.

Jhumpa Lahiri:

Her work felt revolutionary when I came to it, and it still does. She taught me that a short story can do anything. She turned the form on its head. She inspired me to probe deeper, to knock down walls. Her work proves that the mystery of human relationships, of human psychology, remains the essence, the driving force of literature. I am rejoicing at this news. I am thrilled for her; my respect for her is boundless. And I am thrilled for the readers of the world, who will now discover her thanks to this tremendous recognition, and continue to discover her and treasure her into the future.

Lorrie Moore:

The selection of the brilliant Alice Munro is a thrilling one, a triumph for short-story writers everywhere, who have held her work in awe from its beginning. It is also a triumph for her translators, who have done excellent work in conveying her greatness to those not reading in the English she wrote down. This may have to do with her enduring themes and sturdy if radical narrative architecture, but these qualities seem to have been served well by careful translation. If short stories are about life and novels are about the world, one can see Munro’s capacious stories as being a little about both: fate and time and love are the things she is most interested in, as well as their unexpected outcomes. She reminds us that love and marriage never become unimportant as stories—that they remain the very shapers of life, rightly or wrongly. She does not overtly judge—especially human cruelty—but allows human encounters to speak for themselves. She honors mysteriousness and is a neutral beholder before the unpredictable. Her genius is in the strange detail that resurfaces, but it is also in the largeness of vision being brought to bear (and press on) a smaller genre or form that has few such wide-seeing practitioners. She is a short-story writer who is looking over and past every ostensible boundary, and has thus reshaped an idea of narrative brevity and reimagined what a story can do.

Joyce Carol Oates:

A wonderful writer, whom I first began reading in the nineteen-sixties, when I lived in Ontario, Canada. Alice Munro has always been, among her other attributes, “a writer’s writer”—it is just a pleasure to read her work. And how encouraging to those of us who love short stories that this master of the realistic, “Chekhovian” short story is so honored. In a world so frantically politicized and partisan, the achievement of Alice Munro is truly exceptional.

Roxana Robinson:

Like Chekhov, Alice Munro never sets out to make a political point. She isn’t sexist, she has no axe to grind. She’s simply bearing witness to the human experience, reporting from the front lines. Yet she is making a political point, one that’s radical because it’s so enormous and so unsettling. The point is that girls and women, even those who lead narrow and constricted lives, those who wield no influence, who have a limited experience in the world, are just as significant and important as boys and men, those who take drugs, ride across the border, drift down the river, or hunt whales. Women’s lives, too, are driven by the great forces that drive all important experience. As it turns out, all those forces are internal: rage, love, jealousy, spite, grief. These are the things that make our lives so wild and dramatic, whether the backdrops are harpoons or swing sets. The great experiences can be set anywhere: a dentist’s office, a neighbor’s living room, a country road at night. It’s those propulsive, breathtaking, suffocating forces inside us that make those moments so vivid and shocking, it’s what’s inside us that cracks the landscape open, shocking and illuminating like a streak of lightning. She showed us that, Alice Munro.

What we all lead are ordinary lives with extraordinary passages. It’s Munro who reminds us of this, and that the extraordinary is experienced by women as often as by men, and it needn’t take place on a whaling ship. Piano teachers, divorced professors, country doctors, solitary widows in the country—all those small and insignificant people lead lives of enormous drama. Women lead lives of enormous drama. She has made that into fact.

Photojournalist Abigail Heyman, 1942-2013

http://www.nytimes.com/slideshow/2013/06/08/arts/20130608Heyman-obit.html?ref=design

“I have been a girl child and, in my expectations, a mother . . . I have tried to be prettier than I am. I have been treated as a sex object, and at times I have encouraged that. I have been married and have seen my husband’s work as more important than my own.”

Her work as a photographer, she said, reflected “the conflicts inherent in growing up female” and “the conflicts inherent in trying to change.”

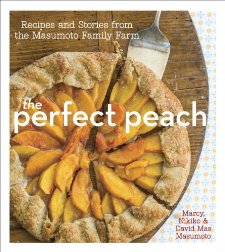

The Perfect Peach: An Interview with Mas Masumoto

NB: Reprinted (so to speak) from the Summer 2013 Eden, the quarterly journal of California Garden and Landscape History Society, www.cglhs.org. Photo: Staci Valentine, from: David Mas Masumoto, Marcy Masumoto, and Nikiko Masumoto, The Perfect Peach: Recipes and Stories from the Masumoto Family Farm (10 Speed Press, 2013)

The Perfection of the Peach: An Interview with Mas Masumoto

(Note: David Mas Masumoto’s replies to my questions during a May 7, 2013, telephone interview; the following are not direct quotations. Rather, they are summarized responses, as per Mr. Masumoto’s request.)

Paula M. Panich: “I farm stories; my main story is about trying to grow the perfect peach,” you write in Wisdom of the Last Farmer.

Mas Masumoto: It’s almost a mantra for small, sustainable organic farmers. We don’t do it for money. Farming stories means you bring in the entire complex—working with nature, the land, the family, the larger social issue of the history of the farmworkers, their wages, and one’s own personal legacy, the history of my grandparents coming from Japan . . .

Q. Was it difficult to publish your first book (Epitaph for a Peach)? That is, making an essentially private act of writing in a journal suddenly public?

A. It was a huge decision. Farmers work independently, individually, privately. You’re surrounded by hundreds of plants, not people. To allow a personal and private life to go public was a big decision for me and for the family. We are, after all, a family farm.

As a writer, though, you want to strike a nerve with personal thoughts and interests, and you do that by revealing yourself. You want to connect with your audience, your readers.

As farmers, you don’t really connect except vicariously through your produce . . . but the whole story of farming has evolved. There’s transparency now. People are interested in food safety. More and more consumers are interested in the backstory of food. The small family farm is well positioned for this.

Q. You have written in Wisdom of the Last Farmer: “[Our farm] stands for the relationship between good food, good stewardship of the land, great love for the natural world and the continuity of life.” And I would add great generosity.

A. There’s a constant and terrifying and wonderful dichotomy in our world: the notion of change. Part of me wants to keep this land exactly the same as it has come down to me. But, for example, the path of the high-speed rail line will cut through the heart of the Central Valley. This will happen. Accepting this is a part of change. The high-speed rail will connect rural and urban California, for good and for bad. It’s good to have this pair of opposites.

People will see a very different kind of agriculture from what they see on Interstate 5. They’ll see smaller farms and far more diverse agriculture. The train will provide a window with a new view of the work we do.

The train will be about ten miles west of those of us in Del Rey. Of course if the path of the train was proposed to cross through the heart of my farm, I would feel differently! But it will come close enough.

It was interesting two years ago when I went to Japan. A high-speed rail line now connects its southernmost island, Kyushu, a very agrarian place not unlike the Central Valley of California, to the mainland. It creates an interesting dynamic, this island now connected to the rest of Japan.

Now we will have rural California—this “other” California—connected by train.

Q. A sad, poignant note from your book Four Seasons in Five Senses describes how you remember a twenty-pound box of peaches selling for two dollars in 1961 and for two dollars in 2001.

A. We must recognize the challenges of the economic forces of what we do. At the same time, that’s not why we do it. It’s a paradox, a dilemma, two forces not working together. But it’s this very interface of life that brings action. If I farmed just for money, or just for aesthetics—that would be one thing. But it’s the median point—the in-between place—that brings the most flavor to life, the dynamic. And from this place I get energy and passion. It’s a challenge and a curse, but at the same time, it brings fantastic joy.

Q. Please tell us about your latest book, The Perfect Peach: Recipes and Stories from the Masumoto Family Farm, written with your wife, Marcy Masumoto, and your daughter, Nikiko Masumoto.

A. It’s a peach cookbook, with twenty essays and fifty recipes, along with photographs. My wife and daughter wrote the headnotes and so forth to the recipes, and I wrote the essays.

It’s a literary cookbook about the farm and our peaches connected to recipes. So it’s not just about peaches in recipes, but also about the relationship of the recipes to death, sweat—and much else. How will all of that add flavor to a recipe for peach preserves?

We make all sides come together. We cannot separate the flavors: They are in all of our stories.

* * *