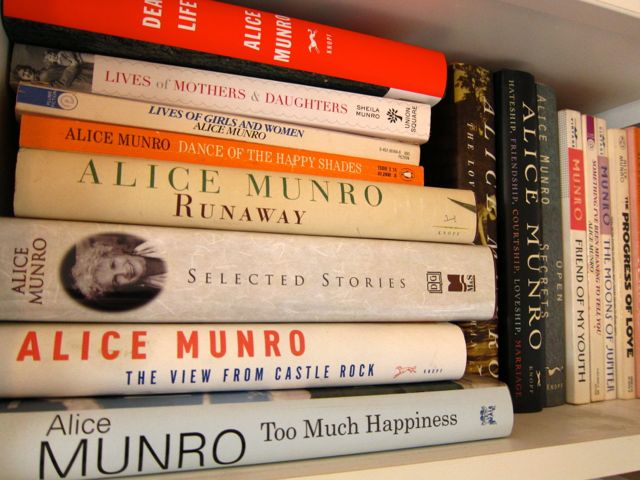

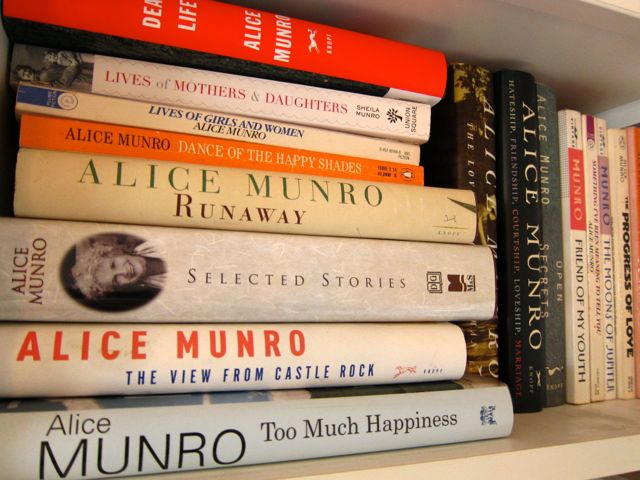

This is my Alice Munro bookshelf. Every book published, at least in this country. I began reading her a quarter of a century ago. I not only love her writing — that’s a given — but I will be forever grateful to her for the opening and clearing of my own writerly voice. She has shown what women think, how they work, how they relate to each other across generations, and what they think of men. What they really think of men. Everything is very complicated, I can tell you.

This was on the New Yorker Blog — writers you may know weighing in on her astonishing body of work. Her short stories are more resonant of life than most contemporary novels. Everyone quotes it, but it’s worth repeating: Writer Cynthia Ozick said it many years ago: She is our Chekhov. This Nobel news yesterday — it’s as good as it gets.

Margaret Atwood:

As I wrote in my introduction to her “Collected Stories”:

Through Munro’s fiction, Sowesto’s Huron County has joined Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County as a slice of land made legendary by the excellence of the writer who has celebrated it, though in both cases “celebrated” is not quite the right word. “Anatomised” might be closer to what goes on in the work of Munro, though even that term is too clinical. What should we call the combination of obsessive scrutiny, archaeological unearthing, precise and detailed recollection, the wallowing in the seamier and meaner and more vengeful undersides of human nature, the telling of erotic secrets, the nostalgia for vanished miseries, and rejoicing in the fullness and variety of life, stirred all together?

Alice and I have been friends since 1969, when her collection of stories “Dance of the Happy Shades” and my collection of poems “The Circle Game” were both published, and I slept on her floor during a visit to Victoria. A lot of Canadians began with short stories then, because it was so hard to get novels published in Canada in the sixties. We both got our start through Robert Weaver’s CBC radio show, “Anthology.” Canadians will be thrilled, Alice will be bowled over, and we will all have a party once she has made her way out of the coat closet, where she has probably gone to hide.

Julian Barnes:

Alice Munro can move characters through time in a way that no other writer can. You are not aware that time is passing, only that it has passed—in this, the reader resembles the characters, who also find that time has passed and that their lives have been changed, without their quite understanding how, when, and why. This rare ability partly explains why her short stories have the density and reach of other people’s novels. I have sometimes tried to work out how she does it but never succeeded, and I am happy in this failure, because no one else can—or should be allowed to—write like the great Alice Munro.

Sheila Heti:

In this vast country without a vast number of people, there are few (for me, anyway) cultural heroes. Glenn Gould is one of them. Alice Munro is another. I think of them all the time, actually. They represent something similar: consistency, seriousness, an uncompromising attitude, and work that is daunting, single-minded, and perfect.

She has always done what she has wanted to, in the way she has wanted to. You look at her and think, Of course, just put all of your intelligence and sensitivity and vitality into your work in a consistent way. There is nothing else. She lives in a small town, has had the same agent since the seventies, doesn’t review books or do many interviews. She seems not to waste her time. She just goes straight to what matters most.

I don’t know when I first read Munro. Probably in school. Certainly her books were always around the house. In Canada, she’s just in the atmosphere, like the Queen.

At a certain point in my early twenties, I wrote a fan letter to Alice Munro. I don’t remember what it said, but I remember how thrilled I was, many months later, to receive a card in the mail with a handwritten thank you in beautiful script, as gracious as anything. She seemed surprised, as though never before had a stranger told her that her stories could mean so much. How alive and unjaded! She must have sent out hundreds, if not thousands, of handwritten cards over the years. It showed me that a writer could be kind and still be a master. One didn’t have to play the aloof or superior game. Indeed, the best writers are probably the best because they have a surfeit of love and generosity toward the world, not the reverse.

In Canada, you can’t make a spectacle of yourself. You have to let other people make a spectacle of you for you. So it’s moving that the answer to her book “Who Do You Think You Are?,” published when she was forty-one (and it’s the question asked of any Canadian person who aspires to anything great) can be, that same number of years later, “The winner of the Nobel Prize.” Not that this would ever be her answer. But it’s wonderful that it can be ours.

Jhumpa Lahiri:

Her work felt revolutionary when I came to it, and it still does. She taught me that a short story can do anything. She turned the form on its head. She inspired me to probe deeper, to knock down walls. Her work proves that the mystery of human relationships, of human psychology, remains the essence, the driving force of literature. I am rejoicing at this news. I am thrilled for her; my respect for her is boundless. And I am thrilled for the readers of the world, who will now discover her thanks to this tremendous recognition, and continue to discover her and treasure her into the future.

Lorrie Moore:

The selection of the brilliant Alice Munro is a thrilling one, a triumph for short-story writers everywhere, who have held her work in awe from its beginning. It is also a triumph for her translators, who have done excellent work in conveying her greatness to those not reading in the English she wrote down. This may have to do with her enduring themes and sturdy if radical narrative architecture, but these qualities seem to have been served well by careful translation. If short stories are about life and novels are about the world, one can see Munro’s capacious stories as being a little about both: fate and time and love are the things she is most interested in, as well as their unexpected outcomes. She reminds us that love and marriage never become unimportant as stories—that they remain the very shapers of life, rightly or wrongly. She does not overtly judge—especially human cruelty—but allows human encounters to speak for themselves. She honors mysteriousness and is a neutral beholder before the unpredictable. Her genius is in the strange detail that resurfaces, but it is also in the largeness of vision being brought to bear (and press on) a smaller genre or form that has few such wide-seeing practitioners. She is a short-story writer who is looking over and past every ostensible boundary, and has thus reshaped an idea of narrative brevity and reimagined what a story can do.

Joyce Carol Oates:

A wonderful writer, whom I first began reading in the nineteen-sixties, when I lived in Ontario, Canada. Alice Munro has always been, among her other attributes, “a writer’s writer”—it is just a pleasure to read her work. And how encouraging to those of us who love short stories that this master of the realistic, “Chekhovian” short story is so honored. In a world so frantically politicized and partisan, the achievement of Alice Munro is truly exceptional.

Roxana Robinson:

Like Chekhov, Alice Munro never sets out to make a political point. She isn’t sexist, she has no axe to grind. She’s simply bearing witness to the human experience, reporting from the front lines. Yet she is making a political point, one that’s radical because it’s so enormous and so unsettling. The point is that girls and women, even those who lead narrow and constricted lives, those who wield no influence, who have a limited experience in the world, are just as significant and important as boys and men, those who take drugs, ride across the border, drift down the river, or hunt whales. Women’s lives, too, are driven by the great forces that drive all important experience. As it turns out, all those forces are internal: rage, love, jealousy, spite, grief. These are the things that make our lives so wild and dramatic, whether the backdrops are harpoons or swing sets. The great experiences can be set anywhere: a dentist’s office, a neighbor’s living room, a country road at night. It’s those propulsive, breathtaking, suffocating forces inside us that make those moments so vivid and shocking, it’s what’s inside us that cracks the landscape open, shocking and illuminating like a streak of lightning. She showed us that, Alice Munro.

What we all lead are ordinary lives with extraordinary passages. It’s Munro who reminds us of this, and that the extraordinary is experienced by women as often as by men, and it needn’t take place on a whaling ship. Piano teachers, divorced professors, country doctors, solitary widows in the country—all those small and insignificant people lead lives of enormous drama. Women lead lives of enormous drama. She has made that into fact.