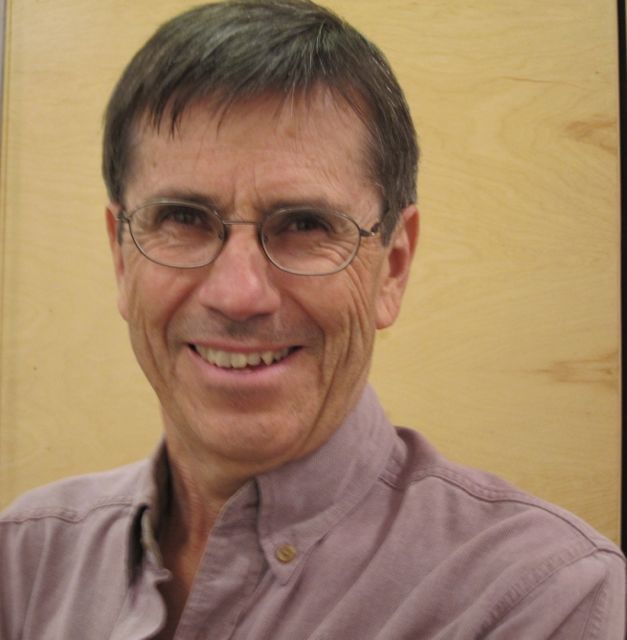

Photographer, writer, and cultural geographer Don J. Usner was a speaker at FUZE-SW, Santa Fe, New Mexico’s first food conference, held in early November this year (2013).

He and another accomplished writer, Carmella Padilla (The Chile Chronicles: Tales of a New Mexico Harvest, and many other books) came to the podium together to address the collective memory of their New Mexican childhoods. Here is the title of their joint talk: Tales We Heard Around the Kitchen Table: Growing Up With Chiles.

It’s déclassé to harbor jealousy over the childhoods of others, but there it is. They were both full of joy and remembrance of chile harvests and extended family tables with fresh, roasted autumn-harvested chiles.

But I happened to speak to Don Usner in passing at lunchtime; he mentioned a book of his, published in 1995, and the hope he has for finding a new publisher willing to keep it in print. Here it is:

Don Usner’s home place is Chimayo, the Hispanic village found on the high road to Taos, home to the famous (and iconic) Santuario de Chimayo, and to traditional weavers and weaving studios. I first travelled to Chimayo thirty years ago to visit the Santuario; a couple of years later I returned to write about the Trujillo family of weavers at Centinela Traditional Arts (www.chimayoweavers.com) for a magazine article about the Hispanic weavers of Northern New Mexico.

Like thousands and thousand of visitors, I was enchanted by everything I saw in Chimayo, and still am. (Including Rancho de Chimayo, where one must have green chile stew; www.ranchodechimayo.com)

Don Usner spent the early 1990s photographing the elders of his community and gatherings stories. His subjects included his beloved grandmother, Benigna Ortega Chavez, other relatives, and their neighbors. Alas, the viejitos drew a generalized veil over the past in response to his questions at the beginning of his research.

One day, when he was sitting at Amanda Trujillo’s kitchen table, she said to him: “‘Oh, I have something you may be interested in.”‘

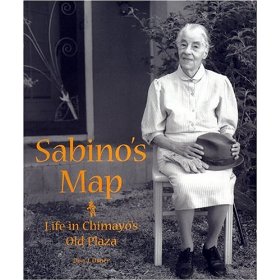

She rose from the table and returned with a rolled up piece of paper. It turned out to be a map of Chimayo’s old plaza, from the 1950s, hand-drawn and annotated by her late husband, Sabino Trujillo. It was Usner’s key to the kingdom.

Sabino’s map was a piece of folk art, as Usner says, a “picture that matched his [Sabino’s] mental image of the old plaza where he grew up in the early decades of the twentieth century.”

When the viejitos were presented with a copy of the map, the treasure houses of memory, story, and imagination were opened to Usner. The result is this rich, moving book, Sabino’s Map: Life in Chimayo’s Old Plaza (Museum of New Mexico Press, 1995).

I don’t keep it far from me. I pick it up, and read, for example, a story from Don Usner’s grandmother, Benigna Chavez:

Bernardo Abeyta was the one who built the Santuario. He was out watering his fields one day when he found an image of Señor de Esquipulas in the barranco. He saw a light and went over, and there was a little crucifix with Señor de Esquipulas in a cave. He took it to his house and put it there, but in a few days, it disappeared and went back to the fields again. He brought it back home, and it went out to the fields again, back where he found it by the river there — you know, down in those fields where they have mass now . . .

This is a rare work of fluid, storytelling scholarship. Usner has tracked the history of the plaza and its people through historical documents — wills and other legal papers, as well as birth and death records. He also pored through old photographs, letters, and notes. And he listened — carefully, and patiently.

The book is a mix of old photographs along with his own, which are moving, and beautiful. (Look at some of his more recent images of Chimayo on the New Yorker site.)

This is a book only an artist born in the heart of a culture could have written and photographed. It is a cultural treasure, a gift to the world coming from a refined heart and mind serving forth stories about politics, agriculture, religion, festivals, ghosts, witchcraft, and family.

Here is a memory, culled from many informants, of Usner’s great aunt, Bonefacia, known as Tia Bone:

“Bonefacia told the dichos, refranes, and cuentos (sayings and stories) that her ancestors carried over from the Old World, and she kept the family history in her memory, reciting stories for a multitude of nieces and nephews. Bonefacia also indulged a passion for roses, cultivating the sweet rosas de Castilla that plaza elders remember so dearly. She was the first person in the area to grow roses . . .

“Bonefacia refused her one offer of marriage, which came from a man who had murdered his wife. ‘Oh, one time a man asked Bonefacia to marry him [Don Usner’s grandmother told him], when she was already a full-grown woman, not so young. I remember when he asked her. It made Tia Bone very mad — she didn’t want to marry, ever. And this man had killed his wife. She said to him—she was very brave—‘How come you killed the wife you had?’ And she refused to marry him. And my father and Tio Nicasio, they said, ‘That Bone, she is fearless!'”

This may be the history of the Chimayosos and their land, but it is the story of a shared humanity cradled in a beloved home landscape.