Among the plants rooted in California is the genus Arctostaphylos, made up of evergreen shrubs commonly known by the Spanish folk name of manzanita or “little apple” for the small, round nutritious fruit beloved of bears, coyotes, foxes, quail, and other animals, including human beings. Californian native peoples made a refreshing seasonal cider from the berries, and manzanita jelly is cooked up to this day.

California is manzanita central. All but three of the ninety species found in the wild are endemic to California; a few species are found north into Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia, east to the Rocky Mountains, in the non-desert parts of Nevada, Arizona, and Texas, and south into Central America. Western gardeners (but not low-desert-dwellers) have a wide choice of garden-worthy forms to choose from, many of them naturally occurring variants, or “intraspecies taxa,” as one taxonomist prefers.

One of those California species, Arctostaphylos uva-ursi, has a “cool-temperate physiology” (in the words of manzanita specialist Philip V. Wells) and is circumboreal—that is, found around the world at northern latitudes, including Alaska, Colorado, Canada, the Great Lakes, Russia, and Siberia. In California, the species is found along the Big Sur coast and north to Del Norte County. It has also been found at the summits of two Guatemalan volcanoes. It is known in the West by the common name of bearberry and by its Native American name of kinnikinnick.

Linnaeus named bearberry, in 1753, as Arbutus uva-ursi; the Latin species name meant bearberry. In 1763, a French botanist, Michel Adanson, determined that the plant represented a separate genus and published the new name as Arctostaphylos uva-ursi; this new Greek genus name translates into English as bear’s grapes.

Arctostaphylos became a more complex genus following early nineteenth-century collections by European botanists who observed many variants along the Pacific Coast of North America. The taxonomic variation continues to the present day, and the genus is recognized as one of the most complex groups of shrubs in the North American flora.

Here’s the crux of the taxonomic debate: most manzanita have a specific, local natural distribution. It’s sometimes hard to tell one species from another. Yet, they interbreed in the wild, easily and readily wherever natural ranges overlap. The number of species found in the genus depends upon the taxonomist you talk to. In the reckoning of Bart O’Brien, senior staff research associate at Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden in Claremont, California, there are ninety species and 140 named cultivars.

The most recent comprehensive taxonomic treatment of the California flora, The Jepson Manual (UC California Press, 1993) will, however, have a new treatment of Arctostaphylos in 2008, written by Tom Parker, a professor of biology at San Francisco State University, along with his SFSU colleague, conservation biologist Michael Vasey, and Jon E Keeley, research scientist at the USGS West Ecological Research Center in Sequoia, California. They have conducted extensive genetic research on manzanitas, the results of which will modify the current accepted, morphology-based classification of the genus.

According to Tom Parker, the new treatment will involve few name changes, but will include greater descriptions of the relationships among species. The researchers found two new species, and a recognized but unnamed subspecies. One new species is Arctostaphylos gabilanensis, a small tree found in the Gabilan Mountains, on the east side of California’s Salinas Valley; the other is A. ohloneana, a small shrub found in the southern Santa Cruz Mountains. “The morphology [of manzanita] has been good in many cases,” says Parker, “but misleading.” In other words, says Steve Edwards, director of the Regional Parks Botanical Garden in Berkeley, “the plants may look like each other, the groupings may seem natural, but the genetics say you’re wrong.”

When even the taxonomists disagree, what’s a gardener to do? Simply forget the taxonomists and enjoy the plants.

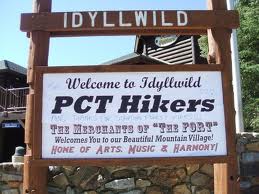

Manzanitas are so well adapted to specific biogeographic spots that they cluster together and dominate their particular landscape in what are called manzanita barrens. In the San Jacinto Mountains above Palm Springs, California, for example, manzanita barrens dominate several hiking trails. The three species in the San Jacinto Mountains are stunning year round. Their striking twisted trunks, and the mahogany-cinnamon color of their smooth bark enlivens the forest, rocks, and boulders in the honeycombed canyons of greens and grays and coffees. Even their silvery skeletons shine.

Alas, the high-living (5,000 feet plus) San Jacinto manzanitas, variants of Arctostaphylos glandulosa, A. pungens, and A. pringlei subsp. drupacea, will not do well in lowland gardens, but no matter. Manzanitas look so much alike that Western gardeners need not suffer a deprivation of plant aesthetics; there is sure to be one nearby that will work in your garden.

Some species bloom in winter, others in spring; many are identified by the shape, color, and composition of the nascent inflorescence. The individual flowers are typical of the heather family (Ericaceae). Bart O’Brien, in California Native Plants for the Garden (Cachuma Press, 2005), noted that people “who take the time to closely observe these blossoms are richly rewarded by their intense honey-like fragrance and their nodding bunches of thick, waxy, white to pink, urn-shaped flowers.”

Manzanita leaves are thick and leathery and come in many tones of bright green through bluish gray and gray green; new stems and foliage often appear in bronze red tones.

But it’s the peeling, cinnamon-kissed, red bark on architecturally fascinating shapes that so appeals. Red is the essential signaling color in the natural world, according to science writer Natalie Angier, and it’s a signal to us, as well. Not all manzanitas have this distinctive bark; some are shaggy and gray. But, when the smooth-barked species shed their annual papery bracelets, that red shines more than ever.

And those twisting shapes? Like almost everything else about manzanita, there’s a complicated story behind their elegant roundish turns and angular shoots. Manzanitas’ nodding flower clusters terminate the growth of a branch. (In most other plants, flowers don’t function as “stop signs.”) Five or six buds may break below the inflorescence, resulting in an infinitely interesting structure.

Manzanitas are not long-lived plants; the average life span of a shrub is twenty-five to fifty years, but some individuals can live for as much as a century. Most, but not all, are chaparral plants; all want their foliage out in the sunlight. You will often see manzanita branches with only a strip of red bark on them, terminating in foliage. The rest of the branch will be gray, marking dead tissue, a survival strategy: plants are not obligated to maintain all that living tissue in shade-shrouded branches, so why waste the energy?

Those barrens in exposed areas are also exercises in species preservation. Some soil substrates are the exclusive province of particular manzanitas. Their tough leaves do duty, too—as “models of adaptation to heat and drought,” O’Brien calls them.

Manzanitas may be tough, with inventive and unusual survival instincts, but they are not equipped to withstand habitat destruction by humans, a particular problem for a plant with a narrow species distribution. A number of species in California are threatened or endangered in the wild. Regeneration of most California species is fire dependent; fire suppression on public lands can cause a sharp decline in populations in the wild. That’s partially the fate of an endangered species endemic to the Santa Cruz Mountains, the Santa Cruz manzanita (Arctostaphylos andersonii).

Another critical species is Pajaro manzanita (Arctostaphylos pajaroensis),

which was endangered as early as the 1930s in its natural range in Santa Cruz and Monterey counties. That’s when, during a misguided attempt at conservation, exotics and introduced natives destroyed at least part of that manzanita’s home, a maritime chaparral ecosystem. Fortunately, some individuals are preserved in the wild, protected by the Elkhorn Slough National Estuarine Research Reserve, south of Santa Cruz.

A remarkable story of manzanita conservation involves the Vine Hill manzanita (Arctostaphylos densiflora) in Sonoma County, California. In 1932, only about a hundred of these manzanitas existed in the wild. In the

following years, these survivors and their progeny were assaulted by agriculture, crankcase oil (applied to control roadside weeds), and bulldozers. After the passionate exhortations of botanist and preservationist James Roof in 1972, the hillside property was purchased by the Nature Conservancy and deeded to the California Native Plant Society. (See Phil Van Soelen’s article in Pacific Horticulture, January 2004).

You might consider, too, reading the lovely elegy for the exquisite Arctostaphylos crustacea subsp. rosei by San Francisco plantsman and garden designer Geoffrey Coffey, “The Lost Manzanitas of Brotherhood Way”. With its crimson-margined leaves, this manzanita may well survive as “a single specimen . . . hemmed in on all sides by weeds and development, actually healthy and robust but all alone, the last of its kind in the San Francisco wild.”

Like almost all native plants everywhere, manzanitas prefer the well-drained soil and climate of their native ranges. Gardeners should educate themselves carefully when choosing a manzanita for their gardens.

Manzanitas are not totally carefree in the garden; they need to be treated with care. Because of their tough leathery leaves, it’s difficult to tell when a plant is suffering; they often simply turn color and, suddenly, die.

In general, manzanitas will not tolerate high mountains and low deserts, alkaline soils, or too much water. When well established, most species are capable of surviving the annual summer drought without irrigation. Almost all prefer full sun.

(N.B.: This article has appeared in different forms in Wildflower,and in Pacific Horticulture. Copyright 2012 by Paula Panich. Flickr photo; thank you, unknown photographer.)

The humble and beautiful Agave deserti. Desert gardeners may await its bloom with anticipation at this time of year, but the Native Peoples of the deserts of Mexico and California depended on it for its delicious roasted “heart,” its tasty flowers, and for its seed, ground into flour.

The humble and beautiful Agave deserti. Desert gardeners may await its bloom with anticipation at this time of year, but the Native Peoples of the deserts of Mexico and California depended on it for its delicious roasted “heart,” its tasty flowers, and for its seed, ground into flour.