Two months ago an article appeared in the New York Times Magazine, delivering, on that chilly Sunday morning, a bit of a shock. Titled, “What is Art For?”, the piece, by Daniel B. Smith, is a survey of the thought and work of the poet, essayist, and thinker Lewis Hyde.It felt to me as a stripping of my most intimate covering, as if somehow a corner of my soul had been exposed in a Sunday newspaper.

Not that thousands of writers and other artists didn’t feel the same way.

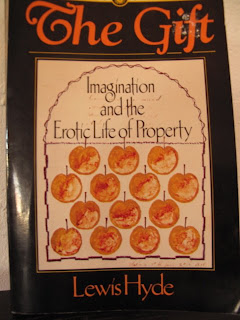

Lewis Hyde published The Gift: Imagination and the Erotic Life of Property, in 1977, when he was still in his thirties. It was seven years in the writing. He was trying to explain to himself why he was drawn to creative work — why anyone, given the commercial nature of modern life, would labor with a full heart on anything as non-remunerative, unvalued and unloved by the world as poetry.

But this seems a ridiculous summary. The book is like a grain of sand one takes within — and by the mysterious working of nature and spirit, it becomes a pearl-in-the-making. The pearl is the layering-in of the inner life — that deep, mysterious and experienced life that almost no one can explain or even describe, unless it makes its shy, quiet voice heard through a work of art.

Hyde takes the reader through mythology, fairy tales, anthropology, linguistics, usury, the anthropology of gift-giving, and analyses of Pound and Whitman and others. But these workings are only the garments, so to speak, to give the deep well of human creativity and inner life some visiblility — those furtive, unbidden and evanescent visitors who come only when the fields of the self are well-prepared and well-watered.

In the Times piece, Daniel Smith writes: “[For] centuries people have been speaking of talent and inspiration as gifts. Hyde’s basic argument was hat this language must extend to the products of talent and imagination too . . .

“Unlike a commodity, whose value begins to decline the moment it changes hands, an artwork gains in value from the act of being circulated — published, shown, written about, passed from generation to generation from being, at its core, an offering.”

This book came to me from a nest of poets, 18 years ago.

It’s not, again, about what The Gift “explains.” It provides a scaffolding, framework, foundation to give hope to those who traffic in the labor of the imagination and spirit — hope that the endeavor is real, essential, and life-giving. In a culture where commodity is all, The Gift is no small package.

The walls of my writing shack are suffused with Lewis Hyde (and not only from this one book). I walk in and can feel the presence of his thought, his articulate defense of the labor of the imagination. The Gift is either on my desk or on the table beside the bed. The walls are encircled with the idea: What happens here is real, and matters.

I might read the same page, or the same chapter for months. (According to Smith, Bill Viola, Margaret Atwood, Donald Hall and Gary Snyder feel much the same. The Gift, by the way, has been rewrapped — with a new [2007] edition and new subtitle: The Gift: Creativity and the Artist in the Modern World — no doubt a nod to the marketplace. But the more people the book attracts, the better.)

I’ll leave you with a couple of paragraphs from the conclusion of The Gift:

“The root of our English word “mystery” is a Greek verb, muein, which means to close the mouth. Dictionaries tend to explain the connection by pointing out that the initiates to ancient mysteries were sworn to silence, but the root may also indicate, it seems to me, that what the initiate learns at a mystery cannot be talked about. It can be shown, it can be witnessed or revealed, it cannot be explained.

“When I set out to write this book, I was drawn to speak of gifts by way of anecdotes and fairy tales because, I think, a gift — and particularly an inner gift, a talent — is a mystery. We know what giftedness is for having been gifted, or for having known a gifted man or woman. We know that art is a gift for having had the experience of art. We cannot know these things by way of economic, psychological, or aesthetic theories. Where an inner gift comes from, what obligations of reciprocity it brings with it, how and toward whom our gratitude should be discharged, to what degree we must leave our gift alone and to what degree we must discipline it, how we are to feed its spirit and preserve its vitality — these and other questions raised by a gift can only be answered by telling Just So stories.”

To read Smith’s piece on Lewis Hyde: www.nyt.com/2008/11/16/magazine/16hyde-t.html

To visit Lewis Hyde’s site: www.lewishyde.com